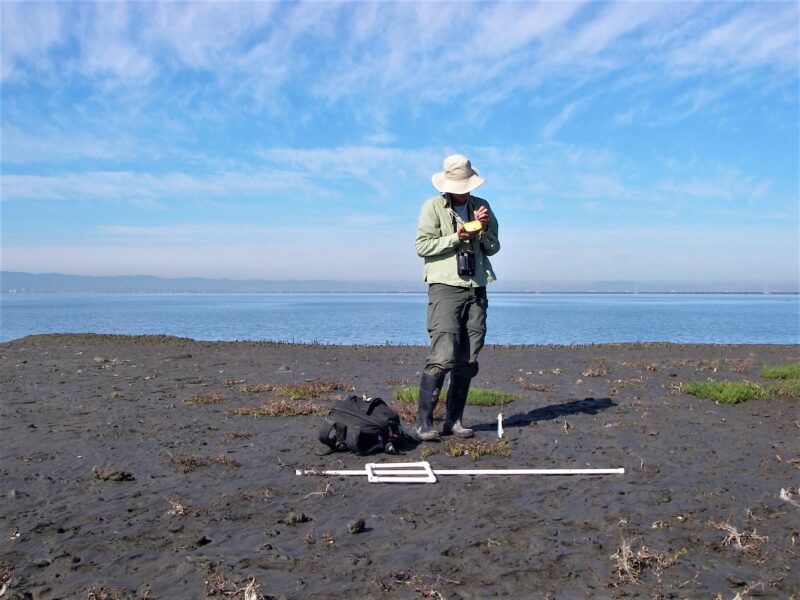

Bair Island restoration site, San Mateo County.

Project History

1800s – early 1900s

San Francisco Bay loses 85% of tidal wetlands to development.

1960s – 1980s

Public opinion shifts from viewing the wetlands as a resource for development and industry to a desire to protect and restore this habitat. Save the Bay, founded in 1961, helps push for the passage of the first wetland protection legislation (McAteer-Petris Act, 1965), which establishes the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC). This is the first coastal zone management state agency in the U.S. charged with wetland protection.

1976

The California State Coastal Conservancy is established. Its mission is to protect and improve natural lands and waterways, help people access and enjoy the outdoors, and sustain local economies along the length of California’s coast and around San Francisco Bay.

1976

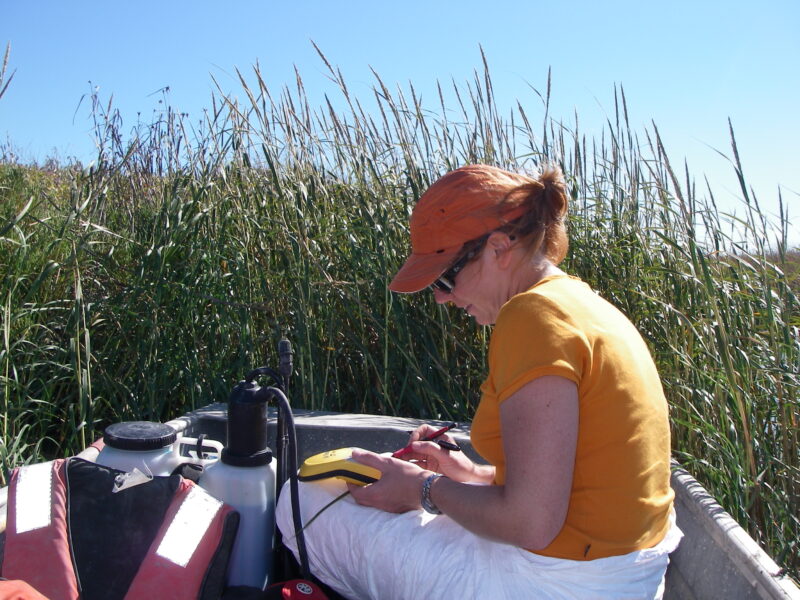

As part of an effort to stabilize dredge spoils, the East Coast species of cordgrass, Spartina alterniflora, is planted in Union City along the Alameda Flood Channel. Despite the best intentions of project planners, this action has unintended consequences.

1980s

Spartina alterniflora, probably already hybridized, spreads rapidly. The changed landscapes are noticed by land managers and tidal wetland restoration crews, as it puts their projects in jeopardy.

1990s

Studies published by researchers at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory discover that the S. alterniflora plant has hybridized. Further studies identify the scope of the problem. Agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and East Bay Regional Park District work to control hybrid Spartina on their lands, but realize that a rhizomatous plant that can spread on the tide needs a regionally coordinated effort.

1992

A study by John Callaway at the University of San Francisco concludes that Spartina alterniflora has a much better chance of becoming established in new areas than the native species, and once established, it spreads more rapidly than the native species. The report includes specifics on how hybrid Spartina adversely affects water flow dynamics, displaces habitat structure for native wetland animals, and disrupts or destroys shorebird and wading bird foraging areas.

2000

The California State Coastal Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service initiate the Invasive Spartina Project (ISP) to head up a multi-agency response effort with the goal of eradicating invasive Spartina from the Bay.

2003

The South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project is created with the purchase of 16,500 acres of salt ponds, funded by state and federal agencies and private foundations. The success of these restoration projects is directly tied to the removal and continued control of invasive Spartina.

2003

The Programmatic Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) is finalized, a broad environmental assessment that provides information for future project decisions, as part of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) decision-making process. This document evaluates the environmental impacts of the project by considering the environment as a whole, including land, water, air, structures, living organisms, and social, cultural, and economic factors. With this report complete, project partners can move forward with monitoring and treatment.

2004

The first Baywide inventory of sites with invasive Spartina is completed, establishing an initial project area of 50,000 acres.

2005

Full-scale treatment of invasive Spartina begins.

2007

The project receives an Outstanding Implementation Project Award from the Friends of the San Francisco Estuary Project.

2007-2012

A Drift Card Study is conducted to help increase the project team’s understanding of dispersal patterns within the Estuary and help predict where to survey for potential new infestations.

2011

The habitat restoration component is launched, focused on installing native plants and features to support California Ridgway’s rail and other tidal wetland species.

2011

Treatment of invasive Spartina is put on hold at eleven sub-areas to balance invasive species management and endangered species management. Five of these sites are untreated until 2018, and six are untreated until 2023, during which time invasive Spartina spreads rapidly, creating a dense monoculture. Neighboring restoration sites are threatened by the continual spread of invasive Spartina pollen, seeds, and rhizome fragments.

2012

The Invasive Spartina Project receives the Outstanding Project Award from the California Invasive Plant Council.

2012

The project team begins creating high-tide refuge islands at selected project sites to protect endangered Ridgway’s rails. These small earthen islands, planted with marsh gumplant and other native plants, are planned in collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and created with assistance from the U.S. Geological Survey and independent contractors H.T. Harvey & Associates.

2015

Using ArcGIS, program managers create one of the most complex and highly-customized mapping and data-tracking systems in the conservation world, earning special recognition from ESRI.

2015

The project receives a second Outstanding Implementation Project Award from the Friends of the San Francisco Estuary Project.

2016

Voters pass Measure AA to create the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority as a way to support major restoration projects, with a goal of restoring 15,000 acres of tidal wetlands around the San Francisco Bay.

2018

The Coastal Conservancy receives its 2018-2022 Biological Opinion for the project, which approves the restart of treatment at five of the eleven sites that had been restricted since 2011. Treatment starts at the “Phase 1” sites.

2019

Cal-IPC joins the project as a nonprofit partner.

2022

To refine field identification of hybrid Spartina, the project team develops a proprietary data-analysis tool that works on hand-held tablets, nicknamed “LinDA” (short for Linear Discriminant Analysis). By incorporating morphological measurements and genetic results from hundreds of prior lab samples collected for DNA analysis, it raises the accuracy of field identification to 85%.

2023

The Coastal Conservancy receives its 2023-2033 Biological Opinion for the project, which approves treatment at the remaining six sites that had been restricted since 2011. Treatment begins on the first three of these “Phase 2” sites.

Since the project’s inception, partners have constructed a total of 82 high tide islands and propagated and planted more than 580,000 native seedlings.