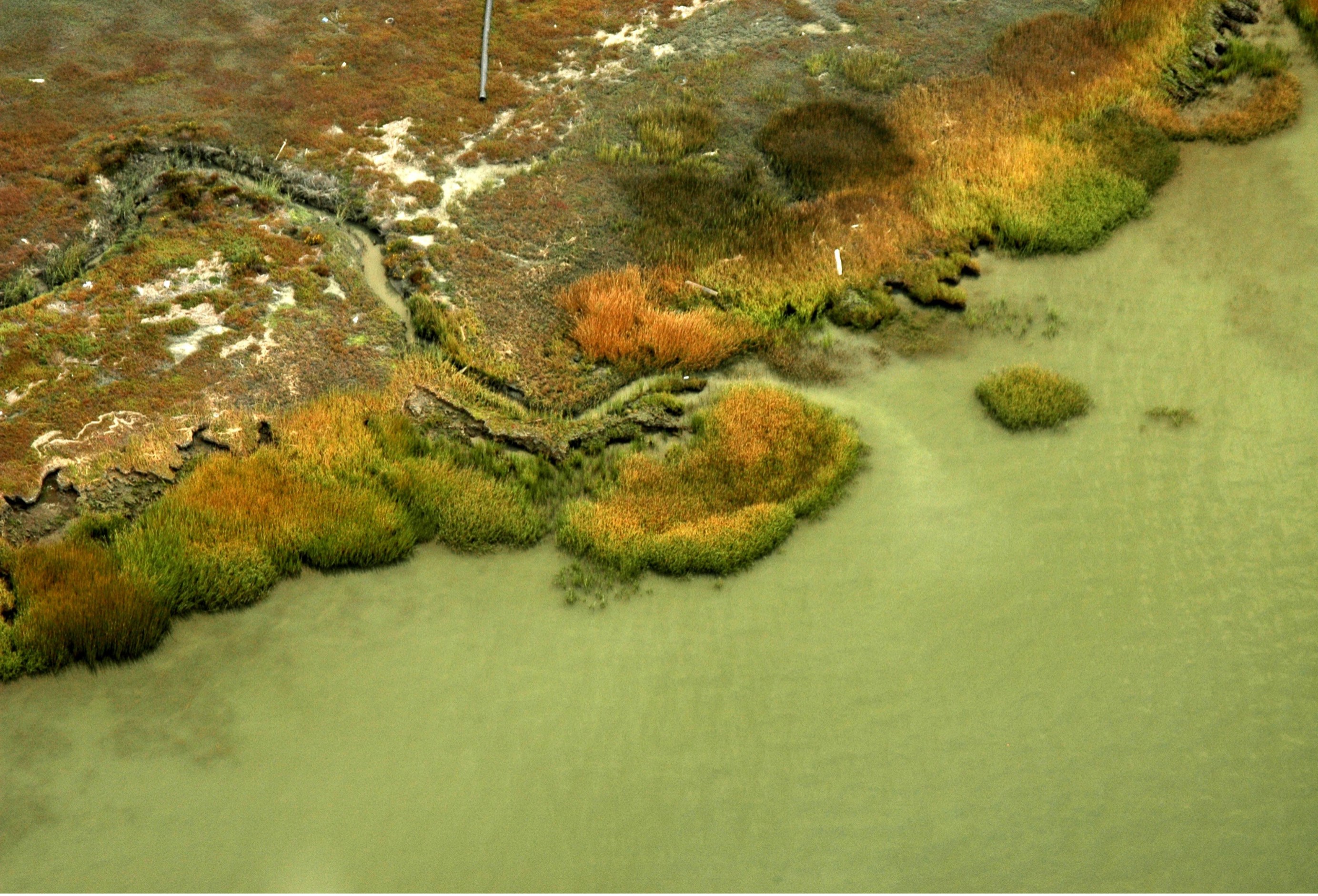

Bair Island restoration site, San Mateo County.

Why is Invasive Spartina a Problem?

Understanding different types of cordgrass

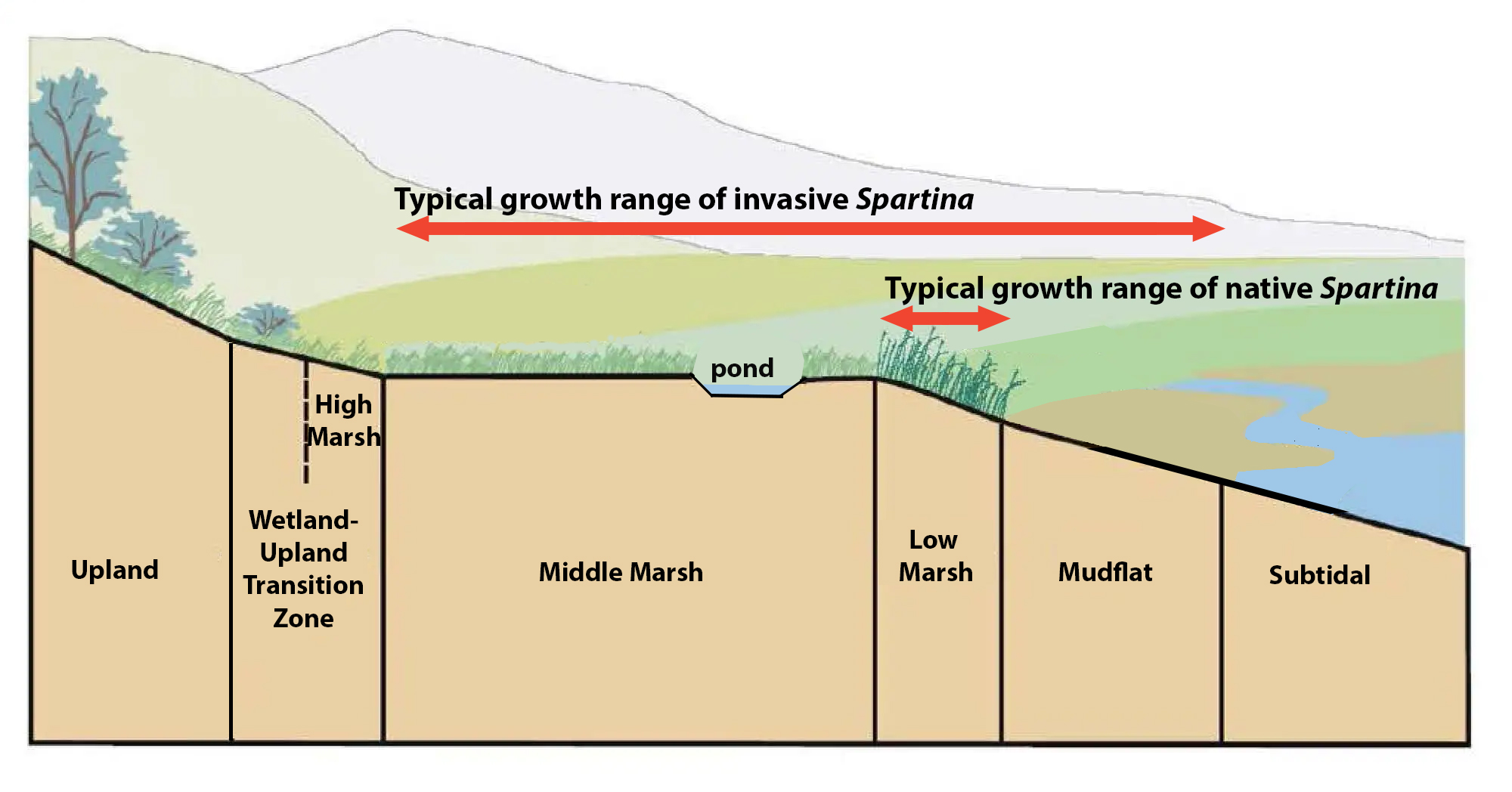

California has a native Pacific cordgrass, Spartina foliosa, a foundational species in the low marsh and pickleweed plain. It is an important early colonizer, and grows in a narrow range, as the lowest elevation plant in the intertidal zone. It has evolved in this region alongside native plants and animals, performing an important ecological role as habitat cover for wildlife. S. foliosa is found only in California and Baja California, and comprises more than 99% of the cordgrass in the SF Estuary.

In the 1970s, the East Coast Spartina alterniflora was introduced as part of an experiment to restore wetlands using dredged material brought in from other locations. The robust East Coast species rapidly stabilized the soupy sediment. Unfortunately, the species hybridized with the native Pacific cordgrass, creating a genetic “hybrid swarm” with classic “hybrid vigor,” where the offspring has more robust characters than either parent.

Compared to native cordgrass, the hybrids may have greater cover (increasing competition to the exclusion of all other native marsh plants), greater height (allows for establishment at lower tidal elevation), greater inflorescence size (allows for pollen swamping of adjacent native cordgrass, as well as greater seed production), and can grow over a greater tidal range.

A few other invasive Spartina species are also under monitoring and treatment in the Bay Area, at a smaller scale: Spartina densiflora, Spartina anglica, and Spartina patens. Read a detailed description about the differences between native and hybrid Spartina types targeted for treatment.

Ecosystems out of balance

A healthy native marsh is a diverse and complex array of natural habitat features, with mudflats, complex tidal channels, large areas of mid and upper tidal marsh, salt pans, and upland areas. Hybrid Spartina can threaten all of these habitat features. If left unchecked, fast-colonizing invasive Spartina can turn an invaded site into a monoculture within a decade.

Several studies (conducted by the Grosholz lab at U.C. Davis, John Callaway at U.C. San Francisco, and others) show that the roots of hybrid Spartina change the soil composition, reducing the benthic invertebrates (by up to 70%) that are essential food for many migratory and resident birds – including the endangered California Ridgway’s rail. Remaining invertebrates shift from surface feeders, available to shorebirds and other consumers, to belowground feeders that are unreachable. The dense network of invasive Spartina roots also prohibits probing feeders from pushing their bills down in the mud to reach their food.

What harm does invasive Spartina cause?

Invasive Spartina outcompetes native tidal marsh species to create a monoculture. It spreads rapidly across open mudflats, creating meadows of cordgrass in place of foraging opportunities for shorebirds, waterfowl, and other aquatic species. It reduces flood control capacity, as dense stands trap and accrete sediment rapidly in unnatural locations, fill in storm water drainages, and cause flooding in adjacent fields, homes, and businesses. These dense hybrid Spartina meadows cause conditions in the marsh (ponding) that promote increased breeding of mosquitoes. The presence of invasive Spartina places shoreline restoration projects at risk of being overwhelmed, making it impossible for native habitat and wildlife to gain a foothold in the restored area.

The Invasive Spartina Project is a collaborative, Bay-wide response to this threat, working together to protect and restore native tidal marshes and mudflats. Please contact us if you are planning or conducting work in tidal marsh and shoreline habitats around San Francisco Bay.